In vitro Wound Healing Potential and Identification of Bioactive Compounds from Aegle marmelos and Mucuna pruriens Methanolic Extract

Volume 1, Issue 1, Pages 17-28

Abstract

Objective:

Traditionally Aegle marmelos and Mucuna pruriens are applied on cuts and wounds. The present study was aimed at exploring the in vitro wound healing potential using CAM assay of Aegle marmelos and Mucuna pruriens and identification of active compounds that may be responsible for its wound healing action.

Methods:

Methanolic extract of Aegle marmelos leaves and Mucuna pruriens seeds were subjected to differential bioguided fractionation. Fractions were screened and flavonoid fraction was finally obtained for further investigation. HPLC analysis and spectroscopic techniques, including ultraviolet (UV) light, infrared (IR) light, mass (MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) were used for identification and confirmation of bioactive compounds. The effects of isolated fractions of Aegle marmelos and Mucuna pruriens on number of new blood vessels and angiogenic inhibition (%) on chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) were assessed.

Results:

Study revealed gallic acid (AM-3-03), quercitin (AM-4-01-01) and rutin (MP-4-03-01-01-01) compounds in the crude methanolic extract and bioactive compounds were identified and confirmed with standard gallic acid, quercitin and rutin using HPLC and UV spectroscopic methods. The isolated fractions promoted angiogenesis as evidenced by in vitro chick chorioallantoic membrane model. The isolated fractions were found to have better angiogenic properties from neovascularization studies. The results were statistically significant when compared to the control group (p < 0.05).

Conclusion:

These findings suggest that bioactive fraction of Aegle marmelos and Mucuna pruriens may enhance faster wound healing in vitro.

Authors

Corresponding Author

Fedelic Ashish Toppo

History

Received 06 November 2025

Revised 22 November 2025

Accepted 04 December 2025

Keywords

Aegle marmelos, Mucuna pruriens, Wound healing, CAM assay, Bioguided fractionation.

Open Access

This is an open access article under the CC BY license https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

INTRODUCTION

Wound healing, or wound repair, is an intricate process in which the skin (or another organ-tissue) repairs itself after injury [1]. The main aim of wound treatment is to achieve a rapid closure of the wound and formation of new blood vessels which will progress the process of wound healing. The rapid closure of wound and formation of new blood vessels can be achieved by wound contraction and angiogenesis respectively [2]. Medicinal plants have been used since time immemorial for the treatment of various ailments of the skin and dermatological disorders especially cuts, wounds and burns [3]. The basic principles of wound healing-minimizing tissue damage, debriding nonviable tissue, maximizing tissue perfusion and oxygenation, proper nutrition and a moist wound healing environment have been recognized for many years. Traditionally leaves of Aegle marmelos (Linn) Correa commonly known as bael (or bel), belonging to the family Rutaceae [4,5] and seeds of Mucuna pruriens Linn commonly known as cowhage plant or kevach, belonging to the family Fabaceae [6,7] are applied on cuts and wounds. Aegle marmelos (AM) is indigenous to India and is abundantly found in the Himalayan tract, Bengal, Central and South India [8]. The leaves are having astringent, laxative, and expectorant [9]. Antimicrobial activity [10] and antioxidant activity [11] have been reported. Mucuna pruriens (MP) is the most popular drug in the Ayurvedic system of medicine [12]. Antioxidant activity [13] and antimicrobial activity [14] have been reported. Use of herbal extract in place of crude herbs started with the aim to control quality and precise dosage for better results. The plant extracts being more efficacious, free from undesirable side effects compared to their pure active principle revalidated the therapeutic benefits of herbs due to totality of constituents rather than the single molecule. To the best of our knowledge, the in vitro wound healing potential of Aegle marmelos leaves and Mucuna pruriens seeds extract or bioactive compounds has not been reported previously. Therefore, this study was aimed at exploring the potential of Aegle marmelos and Mucuna pruriens in enhancing wound healing and identification of putative bioactive compounds responsible for the wound healing action through in vitro process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

All chemicals used were of analytical grade and were used as received without any further purification and were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

Identification and Collection of Plant Material

The seeds of MP were purchased from Bhopal local market and leaves of AM were collected in the month of September from the medicinal garden of VNS group of Institutions, Bhopal (M.P.). These were identified and authenticated by Dr. S. N. Dwivedi (HOD) and voucher specimens (AM:- JC/B/263; MP:- JC/B/264) were deposited in the herbarium of the Department of Botany, Janata PG College, A.P.S. University, Rewa (M.P.). The seeds and leaves were washed, shade dried, powdered moderately and stored in a well closed container.

Extraction of Crude Drugs

The leaves of AM (400 gm) and powdered seeds (500 gm) of MP were extracted with petroleum ether (36 hrs) for defatting. The defatted plant materials were dried and then exhaustively extracted with methanol in soxhlet apparatus. The completion of extraction was confirmed by evaporating a few drops of the extract on the watch glass and ensuring that no residue remained after evaporating the solvent. The methanol extract was concentrated under reduced pressure using a water bath keeping temperature below 50°C to yield semisolid mass and stored in well-closed container for further studies.

Fractionation of the Crude Extract of Methanol

The methanolic extract was chosen based on the in vivo screening results [15,16] and the extract was further subjected to differential bioguided fractionation. The bioactive methanolic crude extract of Aegle marmelos (AM) and Mucuna pruriens (MP) was fractioned by column chromatography on silica gel, successively eluting with petroleum ether, ethyl acetate and methanol and three fractions (AM-3-03 and AM-4-01-01 from Aegle marmelos and MP-4-03-01-01-01 from Mucuna pruriens) were obtained with respective solvents. The fractions were stored appropriately below 50°C until required for further study [17].

HPLC Analysis

Preparation of Standards and Sample

The stock solution (1000 μg/mL) for each standard and sample was prepared by weighing 25 mg of standard, dissolved in methanol and the volume completed to 25 mL in volumetric flask with methanol. The working standard and sample solutions were prepared by diluting the stock solution (1000 μg/mL) to contain concentrations 2.5 μg/mL, 5 μg/mL, 25 μg/mL, 50 μg/mL and 100 μg/mL.

Column Preparation

The C18 column was rinsed with 3 mL methanol HPLC grade + 3 mL acetonitrile (HPLC grade) + 3 mL deionized water at a flow rate 1 mL/min (9 mL of this solvent in 9 min), the column was then rinsed with 3 mL of deionized water (at pH = 2) + 10 mL of deionized water at a flow rate 1 mL/min (13 mL of this solvent in 13 min).

HPLC Conditions

The chromatographic separation was conducted using an gradient systems (Table 1). The standard mixtures (50 μL from each standard) and the cleaned honey samples, were analysed using a Waters (600) HPLC linked with a computer-controlled system. Sample (20 μL) was injected using a manual injector. The flavonoids were detected using a photodiode array detector (PDA), the column used was a reversed phase C18 column (15 cm x 0.46 cm). For analysis by (PDA) detection, UV spectra were recorded from 210–400 nm at a resolution 1.2 nm. In particular, the chromatograms were monitored at 340 nm and 290 nm. The mobile phase was composed of 5% acetic acid in deionized water (solvent A), and acetonitrile HPLC grade (solvent B), at a constant solvent flow rate 1 mL/min.

- Solvent A = 5% acetic acid in deionized water

- Solvent B = Acetonitrile HPLC grade (99.8%).

| Time, min | Flow, mL/min | A, % | B, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | 1:00 | 95 | 5 |

| 15 | 1:00 | 85 | 15 |

| 25 | 1:00 | 85 | 15 |

| 40 | 1:00 | 78 | 22 |

| 70 | 1:00 | 78 | 22 |

| 80 | 1:00 | 75 | 25 |

| 90 | 1:00 | 95 | 5 |

The isolated fraction was further subjected to spectroscopy methods for structure elucidation.

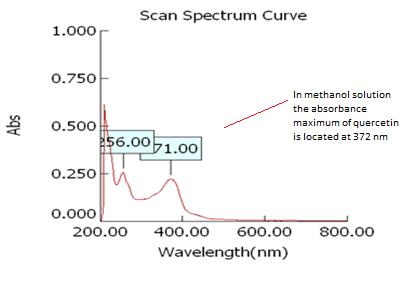

Ultraviolet-visible Spectroscopy

UV-Visible spectrum of the isolated compound was recorded on a UV-Visible spectrometer (Shimadzu UV-160A) at room temperature. About 1 mg of compound dissolved in 20 mL of acetone/chloroform and was used to record the spectrum in the wavelength range of (λ) 200 to 800 nm.

Samples for UV/Vis spectrophotometry are most often liquids, although the absorbance of gases and even of solids can also be measured. Samples are typically placed in a transparent cell, known as a cuvette. Cuvettes are typically rectangular in shape, commonly with an internal width of 1 cm. (This width becomes the path length, L, in the Beer-Lambert law). Test tubes can also be used as cuvettes in some instruments. The type of sample container used must allow radiation to pass over the spectral region of interest. The most widely applicable cuvettes are made of high quality fused silica or quartz glass because these are transparent throughout the UV, visible and near infrared regions. Glass and plastic cuvettes are also common, although glass and most plastics absorb in the UV, which limits their usefulness to visible wavelengths.

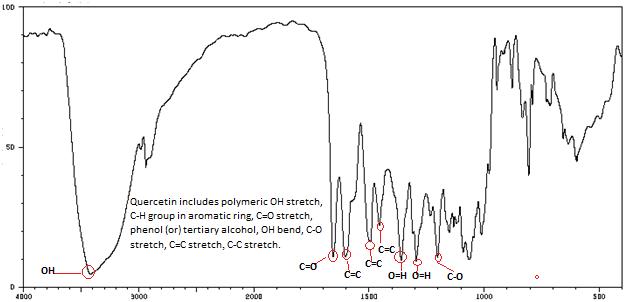

Infrared Spectroscopy

Fourrier-transformation-(FT)-IR spectrum of isolated fraction was recorded by using (FT-IR-Bruker) spectrophotometer for studying the functional groups. The sample compound was fixed in potassium bromide (KBr) disc then the spectrum was measured at wave number ranged from (600–4000 cm-1). The various bands are identified related to their wave numbers.

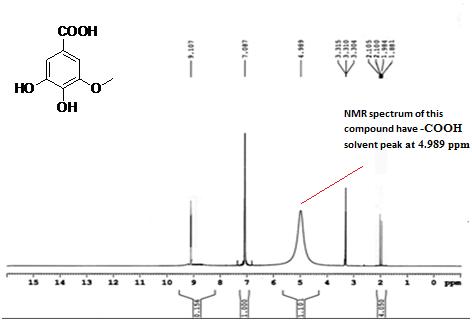

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy

Isolated fraction was dissolved in di methyl sulphoxide and used for Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopic analysis. Sophisticated multinuclear FTNMR Spectrometer model Avance II (Bruker) was used for the study, with a cryomagnet of field strength 9.4 T and 1H frequency 400 MHz. The chemical shifts expressed in ppm were recorded.

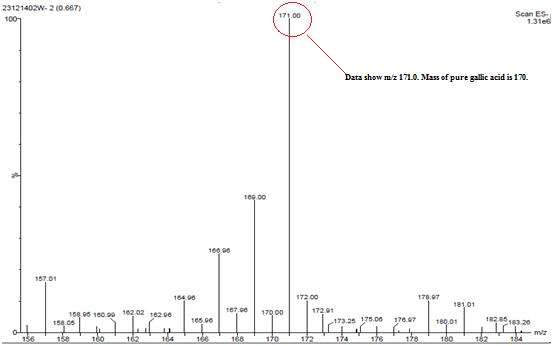

Mass Spectroscopy

Mass spectrometry is a particularly powerful scientific technique because it can be successfully applied even if you have only a tiny quantity available for analysis-as little as 10–12 g, 10–15 moles for a compound of mass 1000 Daltons (Da). Compounds can be identified through mass spectrometry at very low concentrations (one part in 1012) in chemically complex mixtures.

Mass spectra of isolated fraction were recorder on a JEOL SX 102/DA-6000 mass spectrometer/ data system using Argon /Xenon (6 KV, 10 mA) as the FAB gas. The accelerating voltage was 10 KV and the room temperature (27°C). M-nitobenzyl alcohol was used as the matrix unless specified otherwise. The matrix peaks may be metal ions. Ig metal ions such as Na+ are present then peaks may be shifted accordingly. The positive FAB-MS spectra were obtained m/z verses relative abundance after taking 2–4 scans.

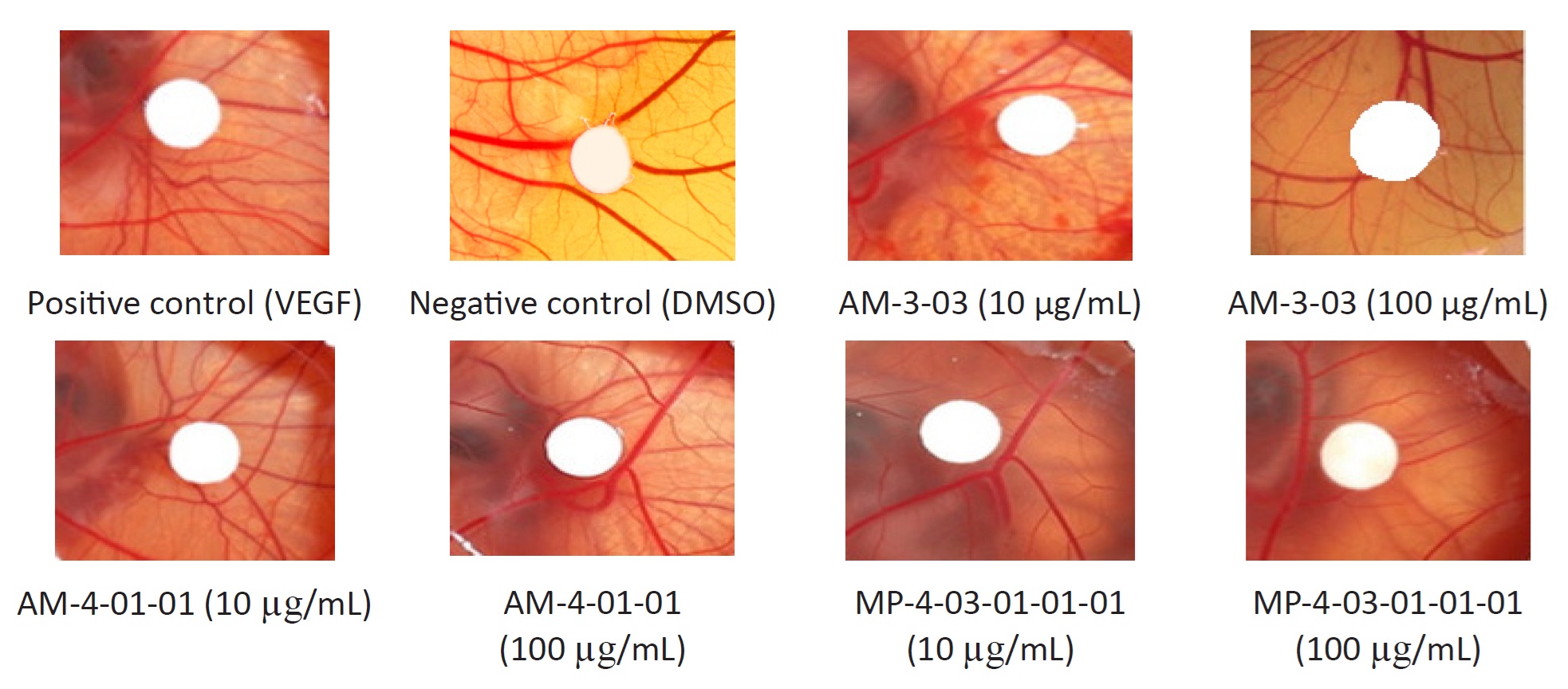

Chick Chorioallantoic Membrane Assay (CAM assay)

CAM assay was carried out for all the extracts according to the assay procedures described previously [18]. 5 days old fertilized chicken eggs were obtained from a local hatchery, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh. About 5 ml of albumin was withdrawn by using a sterile syringe and eggs are allowed for incubation for a period of 6 h to allow the CAM detachment from the outer shell. The isolated fraction were dissolved in DMSO (5% v/v) and loaded in to sterile paper disc at varying concentrations (10, 100 µg/ml). Sterile paper discs loaded with the vehicle were used as negative control. A group of 6 eggs were assigned for each concentration. Later discs are applied on the CAM through a small window (1 × 1 cm) made on the shell. Later, window was closed with the help of and a sterile surgical tape and eggs were allowed for incubation for a period of 48 h. The images of each egg treated CAM were captured and analyzed for blood vessels in the disc application site and the percentage inhibition was calculated [19,20]. A positive control VEGF, which is a potent angiogenic inducer and a negative control DMSO were also tested simultaneously to compare the angiogenic activity of the isolated fractions.

Visual Assessment and Photography

In this assay, the CAM was examined after an incubation period of 48 h, quantitation involves counting the number of CAM vessels around the area of filter paper disk [21]. In general pro-angiogenic stimuli, leads the newly formed blood vessels to appear like a disk in a wheel-spoke pattern. In contrast inhibition of angiogenic stimuli leads to lack of formation of new blood vessel. For the assessment of CAM four quadrants in the area were drawn. The branch point of each blood vessel was counted manually in a clockwise direction in each area of the quadrant.

Statistical Analysis

The results obtained were analyzed by One-way ANOVA to evaluate the significant difference of means among various treatment groups using Graphpad prism 6.0 software. The values are presented as mean ± S.D. A p value less than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

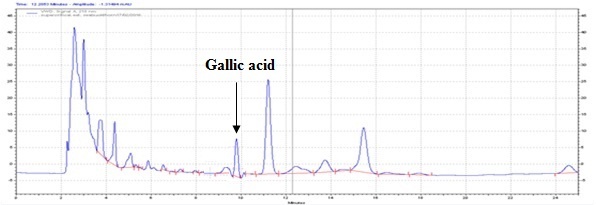

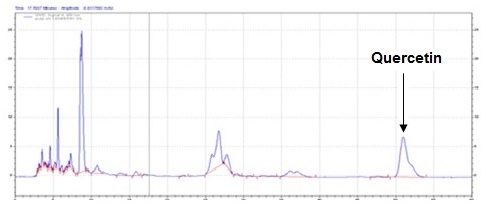

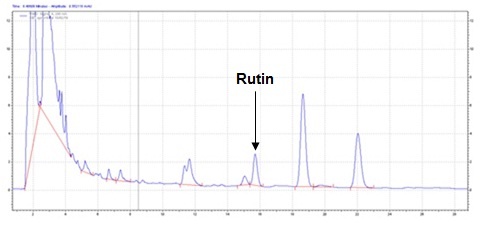

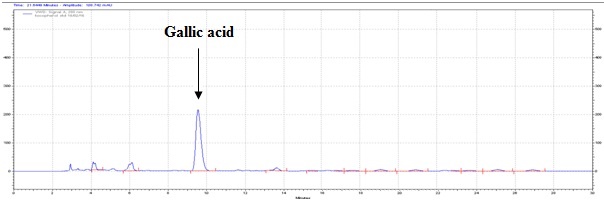

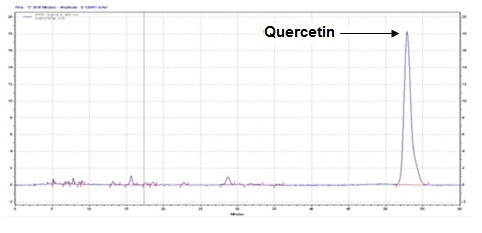

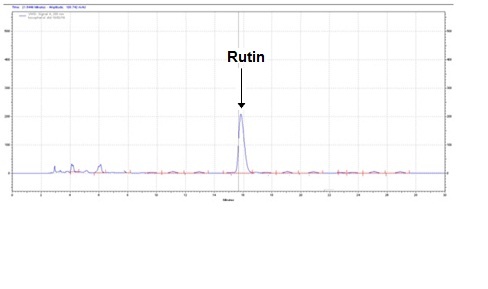

The method developed for HPLC fingerprinting provided a quick analysis of the isolated fraction. The components gallic acid, rutin and quercitin were identified by comparing retention times, with the retention times of gallic acid, rutin and quercitin standards. The conditions used led to a good separation of the peaks which could be identified in the chromatogram as gallic acid (Rt = 9.9), rutin (Rt = 15.9) and quercitin (Rt = 20.6). The chromatograms are shown in Figures 2, 4 and 6. They were identified by comparison with the chromatogram of the reference compounds obtained under the same conditions and the respective UV spectra, obtained on line. The chromatograms are shown in Figures 1, 3 and 5.

The identified peaks were considered to represent only one compound each because the UV spectra at the upslope and down slope inflection points, in each peak, were indistinguishable. The analysis time is an important factor in analytical work and the run time should be reduced to a minimum in order to optimize equipment use and reduce solvent consumption. Although the peak of gallic acid, rutin and quercitin were well resolved under the conditions used for the fingerprinting chromatogram, when we increased the organic modifier content of the mobile phase the peaks of interest were still well resolved but with reduced retention time. The described HPLC procedure could be useful for the qualitative and quantitative analysis of flavonoids in plant materials.

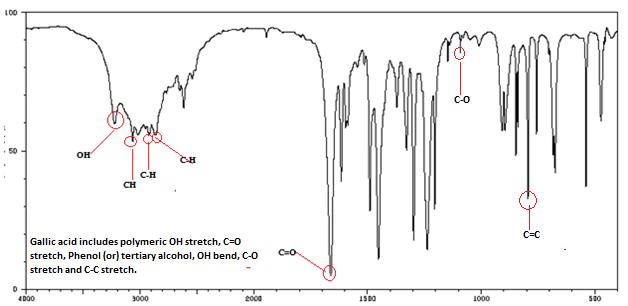

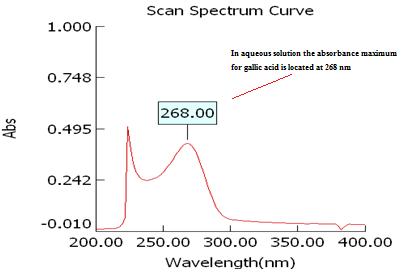

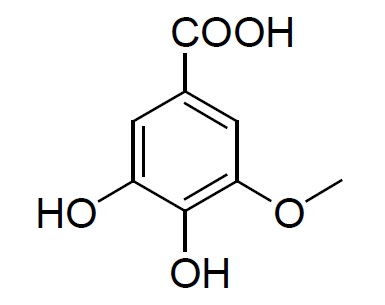

Isolated fraction AM-3-03 was found to be light yellowish in color, melting point 260–262°C and observed yellowish in colour under UV light. Soluble in methanol, ethanol and water, identified as that the compound may be derivative of gallic acid (Figures 7–10) as interpreted from the different spectral data (Table 2).

| Method | Spectral interpretation |

|---|---|

| UVmax | 268 nm |

| IR | Stretching band at 3259.95 cm-1 (s) due to OH stretching; at 3015.23 (s) due to Aromatic CH str.; 2932.28, 2851.91 due to Aliphatic C-H str.; 1704.91due to C=O str.; 71.34, 1072.6 due to C-O str., 1651.08, 1503.42, 1417.91 due to Aromatic C=C; 775.83 due to Aromatic C-H out of plane |

| 1HNMR (ppm) | 7.087 ppm due to s, 2H, ArH; at 9.107 ppm due to H s, 1H, -COOH; at 4.989 ppm due to s, 3H, 3 OH |

| MASS (m/z %) | 171.0 (due to molecular ion) |

| Structure |  3,4-dihydroxy-5-methoxybenzoic acid |

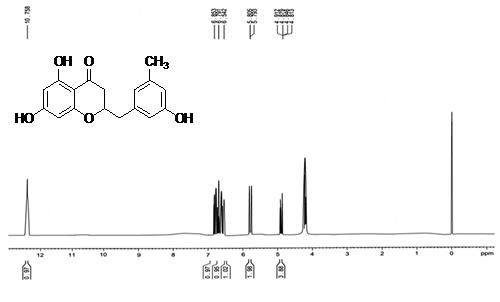

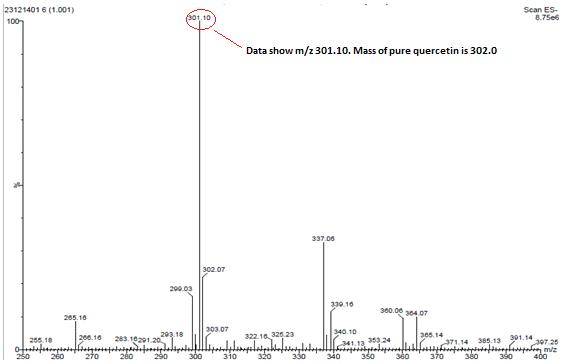

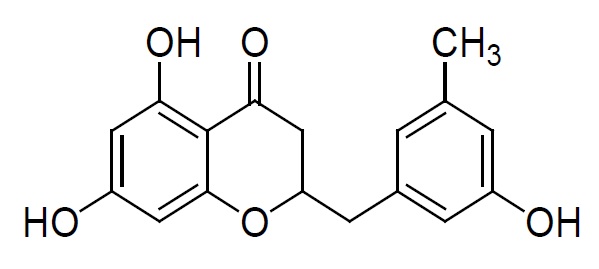

Isolated fraction AM-4-01-01 was found to be pale yellow powder, melting point 311–315°C and observed yellowish in colour under UV light. Soluble in ethanol, methanol, chloroform, DMSO and partially insoluble in water, identified as that the compound maybe derivative of quercetin (Figures 11–14) as interpreted from the different spectral data (Table 3).

| Method | Spectral interpretation |

|---|---|

| UVmax | 256 nm and 271 nm |

| IR | 3495.12 (OH, stretch), 1696.43 (C=O, stretch), 1610.55, 1537.28, 1427.20 (C=C stretch), 1309.07 (OH, In-plane bend), 1246-1199 (C-O stretch), 1023.81 (OH, Out-plane bend), 864.49 (Ar-H, Out of plane bend). |

| 1HNMR (ppm) | 8.04 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 7.95–7.96 (multiplat, Ar-H), 6.37-6.38 (m, 1H Al-OH), 6.17-6.20 (m, 1H, Ar-OH), 5.22-5.24 (m, 2H, Ar-OH), 4.47 (m, 1H, Ar-OH). |

| MASS (m/z %) | 301.2 (Base peak) |

| Structure |  2-(3-hydroxy-5-methylbenzyl)-2,3-dihydro-5,7-dihydroxychromen-4-one |

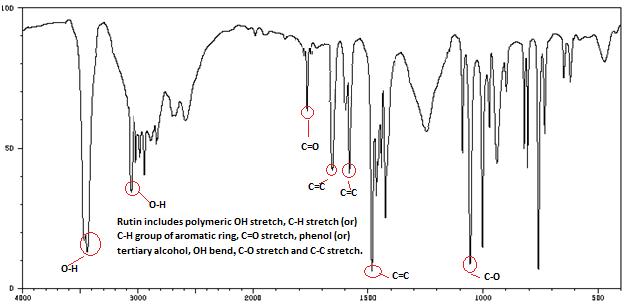

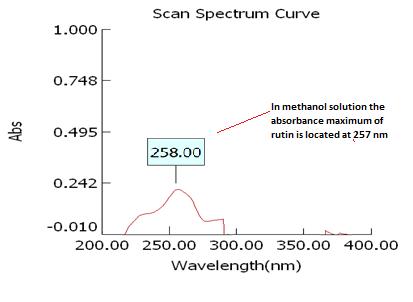

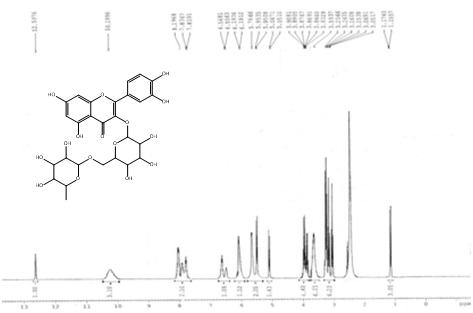

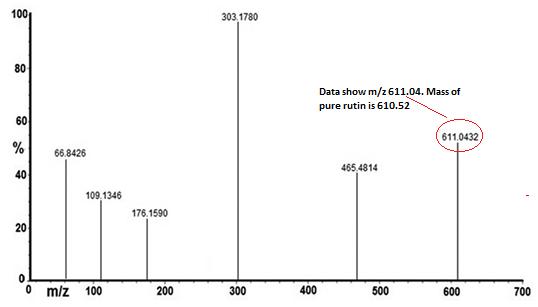

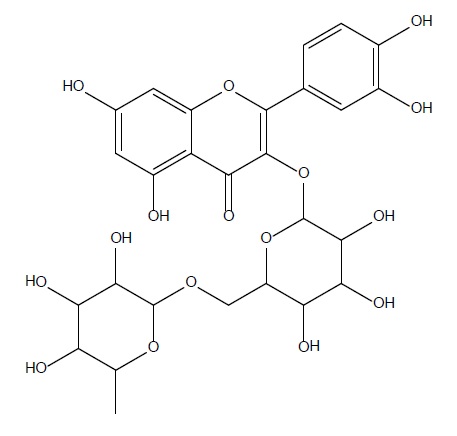

Isolated fraction MP-4-03-01-01-01 was found to be light yellow powder, melting point 311–242–244°C and observed yellowish in colour under UV light. Soluble in ethanol, methanol, chloroform, DMSO and partially insoluble in water, identified as that the compound maybe derivative of rutin (Figures 15–18) as interpreted from the different spectral data (Table 4).

| Method | Spectral interpretation |

|---|---|

| UVmax | 258 |

| IR | C-O-1076.58, C=C-1667.18 & 1473.29, C=O-1729.29, O-H-3423.06 & 3140.24, CH2-OH-1573.25 |

| 1HNMR (ppm) | OH-12.5976 (s, 1H), OH-10.1996 (s, 4H), CH-8.1968 (s, 1H), CH-7.8367 (d, 1H), CH-6.568 (d, 1H), CH-6.1936 (d, 1H), CH-5.9666 (s, 1H), CH2-OH-5.9535 (d, 2H), CH-5.0671 (d, 1H), CH-3.9081-3.8329 (p, 4H), OH-3.5937 (s, 6H), CH-3.2566-3.0517 (triple triplet, 6H), CH3-1.1740 (d, 3H) |

| MASS (m/z %) | 611.04-M scan |

| Structure |  C27H30O16 |

Isolated fractions at different concentrations, along with VEGF as a positive control and DMSO as a negative control, was tested in the CAM assay for its angiogenic activity and it was demonstrated that the CAM assay are versatile tools for the in vitro evaluation of small quantities of natural compounds or isolated compounds, enabling the detection of possible angiogenic or antiangiogenic effects of the test compound to evaluate its property as an angiogenic drug candidature.

After incubation period (Figure 19), VEGF treatment led to a simulation with a strong network of sprouting capillaries and increased vessel density within the ring and treatment with isolated fractions at different concentrations showed the formation of capillaries similar to the VEGF. No changes in vascular structure or density were observed with DMSO. CAM implanted with VEGF showed a significant increase of new blood vessels in the VEGF control group suggests that the added VEGF was the only factor which could have stimulated the ectopic angiogenesis in CAM.

CAM implanted with isolated fractions AM-3-03, AM-4-01-01 and MP-4-03-01-01-01 at 10 µg/mL concentration inhibited angiogenesis by 62.40 ± 8.89%, 46.68 ± 4.51% and 68.35 ± 4.07% respectively, while the higher concentrations of 10 µg/mL showed a moderate degree of angiogenesis inhibition of, by 60.00 ± 5.74%, 28.26 ± 1.58% and 61.14 ± 7.86%, respectively (Table 5). Negative control (DMSO) treatment revealed a smaller number of newly formed blood vessels (8.75 ± 2.28) compared to new blood vessels (36.00 ± 5.58) in positive con-trol (VEGF).

| Treatment | Concentration of extract (µg/mL) | Number of new blood vessels | Angiogenic inhibition (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive control (VEGF) | 36.00 ± 5.58 | 0 | |

| Negative control (DMSO) | 8.75 ± 2.28 | 0 | |

| AM-3-03 | 10 | 14.25 ± 3.81 | 62.40 ± 8.89 |

| 100 | 17.50 ± 2.79 | 60.00 ± 5.74 | |

| AM-4-01-01 | 10 | 19.25 ± 3.25 | 46.68 ± 4.51 |

| 100 | 26.50 ± 1.02 | 28.26 ± 1.58 | |

| MP-4-03-01-01-01 | 10 | 10.75 ± 1.75 | 68.35 ± 4.07 |

| 100 | 15.50 ± 4.96 | 61.14 ± 7.86 |

Angiogenesis is important in normal process such as development of embryo formation of corpus luteum and wound healing [22]. Angiogenesis during wound repair serves the dual function of providing the nutients demanded by the healing tissues and contributing to structural repair through the formation of granulation tissue [23]. The chicken CAM assay revealed a reduction in the antiangiogenic effect. VEGF has endothelial cell-specific mitogenic activity and stimulates angiogenesis in vivo and in vitro [24]. VEGF is an important pro-angiogenic cytokine and improves angiogenesis during wound healing by stimulating the migration and proliferation of endothelial cells through the extra cellular matrix [25]. The methanolic extract being the most bioactive crude extract suggests fully that the compound(s) responsible for the proliferative action may be chemically polar and inorganic because methanol is an inorganic solvent in addition to its polar property. These active compounds belong to the group of flavonoid compounds, this group of compounds is known to be beneficial in wound healing treatment [26]. This potential could be due to the ability to regulate any of the proteins or chemotactic factors involved in the healing process at the molecular level. The evaluation of the molecular mechanism behind this potency requires further studies in the established model which can be extended to wounds of different types and severity. The identified bioactive compounds in the methanolic crude extract of Aegle marmelos and Mucuna pruriens may serve as a lead in the drug discovery and development of a wound healing agent that may enhance wound healing.

CONCLUSION

Angiogenesis, the generation of new capillaries, is a highly restricted, regulated and self-limited activity. VEGF significantly enhanced the neovascularization in the positive control groups as compared with the DMSO-treated group, evidencing its pro-angiogenic activity. Similarly, isolated fractions AM-3-03, AM-4-01-01 and MP-4-03-01-01-01 of Aegle marmelos and Mucuna pruriens also exhibited neovascularization as that of VEGF. In addition, in the treatment group, a significant dose-dependent stimulation of the neovascularization was evident, evidencing its angiogenic property. This study suggests that these isolated fractions could be considered as a useful source of material for human health as an angiogenic agent.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author’s Contribution

Fedelic Ashish Toppo performed the research work, and wrote the manuscript with support from Mahendra C Gunde. Mahendra C Gunde verified the assisted with data interpretation. Both authors discussed the results and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgment

Authors would like to thank VNS group of Institutions, faculty of Pharmacy, Bhopal, India for providing all the necessary facilities and their technical assistance during this work and especially I also extend my thanks to Dr R S. Pawar for guidance.

REFERENCES

| [1] | Marrelli M. Medicinal plants. Plants (Basel). 2021;10(7):1355. Doi: 10.3390/plants10071355. |

| [2] | Darby IA, Hewitson TD. Fibroblast differentiation in wound healing and fibrosis. Int Rev Cytol. 2007;257:143–79. Doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(07)57004-X. |

| [3] | Kumar B, Vijayakumar M, Govindarajan R, Pushpangadan P. Ethnopharmacological approaches to wound healing-exploring medicinal plants of India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;114(2):103–113. Doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.08.010jep.2007.08.010. |

| [4] | George KV, Mohanan N, Nair SS. Ethnobotanical investigations of Aegle marmelos (Linn.) Corr. In: Singh V and Jain AP, Editors. Ethnbot. Med. Plants India and Nepal. Jodhpur: Scientific Publishers; 2003. pp. 29–35. |

| [5] | Dhankhar S, Ruhill S, Balharal M, Dhankhar S, Chhillar AK. Aegle marmelos (Linn.) Correa: a potential source of Phytomedicine. J Med Plan Res. 2011;5(9):1497–1507. |

| [6] | Sreeeramalu N, Suthari S, Ragan A, Raju VS. Ethno-botanico-medicine for common human ailments in Nalgonda and Warangal districts of Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, India. Anna Plan Sci. 2013;2(7):220–229. |

| [7] | Naidu VL, Bahadur AN, Kanungo VK. Medicinal plants in Bhupdeopur forest, Raigarh Chattisgarh Central India. Int J Med Arom Plants. 2014;4(1):6–15. |

| [8] | Manandhar B, Paudel KR, Sharma B, Karki R. Phytochemical profile and pharmacological activity of Aegle marmelos Linn. J Integr Med. 2018;16(3):153–163. Doi: 10.1016/j.joim.2018.04.007. |

| [9] | Kirtikar KR, Basu BD. Indian medicinal plants. 2nd Ed. New Delhi: Periodical Experts Book Agency; 1993. pp. 499–505. |

| [10] | Rani P, Khullar N. Antimicrobial evaluation of some medicinal plants for their anti-enteric potential against multi-drug resistant Salmonella typhi. Phytother Res. 2004;18(8):670–673. Doi: 10.1002/ptr.1522. |

| [11] | Rajadurai M, Prince PS. Comparative effects of Aegle marmelos extract and alpha-tocopherol on serum lipids, lipid peroxides and cardiac enzyme levels in rats with iso-proterenol-induced myocardial infarction. Singapore Med J. 2005;46(2):78–81. |

| [12] | Kumar DS, Muthu AK, Smith AA, Manavalan R. In vitro antioxidant activity of various extracts of whole plant of Mucuna pruriens (Linn). Int J PharmaTech Res. 2010;2(3): 2063–2070. |

| [13] | Tripathi YB, Upadhyay AK. Antioxidant property of Mucuna pruriens Linn. Current Science. 2001;80(11):1378. |

| [14] | Rajeshwar Y, Gupta M, Mazumder UK. In vitro lipid peroxidation and antimicrobial activity of M. pruriens seeds. Iranian J Pharma Therap. 2005;4(1):32–35. |

| [15] | Toppo FA, Pawar RS. Appraisal on the wound healing activity of different extracts obtained from Aegle marmelos and Mucuna pruriens by in vivo experimental models. Niger J Clin Pract. 2016;19(6):753–760. Doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.181364. |

| [16] | Toppo FA, Pawar RS. Wound healing potential of various successive fractions obtained from Aegle marmelos (AM) and Mucuna pruriens (MP) in acid burn wound models: an experimental animal study. Entomol Appl Sci Lett. 2016;3(5):14–22. |

| [17] | Nisar M, Khan S, Dar A, Rehman W, Khan R, Jan I. Antidepressant screening and flavonoids isolation from Eremostachys laciniata (L) bunge. African J Biotech. 2011;10(9):1696–1699. Doi: 10.5897/AJB10.1254. |

| [18] | West DC, Thompson WD, Sells PG, Burbridge MF. Angiogenesis assays using chick chorioallantoic membrane. Methods Mol Med. 2001;46:107–29. Doi: 10.1385/1-59259-143-4:107. |

| [19] | Nassar ZD, Aisha AF, Ahamed MB, Ismail Z, Abu-Salah KM, Alrokayan SA, et al. Antiangiogenic properties of Koetjapic acid, a natural triterpene isolated from Sandoricum koetjaoe Merr. Cancer Cell Int. 2011;11(1):12. Doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-11-12. |

| [20] | Wang S, Zheng Z, Weng Y, Yu Y, Zhang D, Fan W, et al. Angiogenesis and anti-angiogenesis activity of Chinese medicinal herbal extracts. Life Sci. 2004;74(20):2467–2478. Doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.03.005. |

| [21] | Deryugina EI, Quigley JP. Chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane model systems to study and visualize human tumor cell metastasis. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;130(6):1119–1130. Doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0536-2s00418-008-0536-2. |

| [22] | Taylor S, Folkman J. Protamine is an inhibitor of angiogenesis. Nature. 1982;297(5864):307–312. Doi: 10.1038/297307a0. |

| [23] | Martin A, Komada MR, Sane DC. Abnormal angiogenesis in diabetes mellitus. Med Res Rev. 2003;23(2):117–145. Doi: 10.1002/med.10024. |

| [24] | Ng YS, Krilleke D, Shima DT. VEGF function in vascular pathogenesis. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312(5):527–537. Doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.11.008. Epub. |

| [25] | Ferrara N. Molecular and biological properties of vascular endothelial growth factor. J Mol Med (Berl). 1999;77(7): 527–543. Doi: 10.1007/s001099900019. |

| [26] | Agrawal AD. Pharmacological activities of flavonoids: a review. Int J Pharm Sci Nanotech. 2011;4(2):1394–1398. Doi: 10.37285/ijpsn.2011.4.2.3. |