Investigating and Exploring the Neuroprotective Effect of Metformin, Vitamin E and Co Enzyme Q10 in Neonatal Rat Model of Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy

Volume 1, Issue 1, Pages 1-9

Abstract

Objective:

This study examined the effects of metformin, vitamin E, and coenzyme Q10 [CoQ10] administered individually and in combination in a neonatal rat model of Neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) induced on postnatal day [PND] 7 by unilateral carotid artery ligation followed by hypoxia. Behavioral, biochemical, neurological and histopathological parameters were evaluated through postnatal day 14.

Methods:

We analyzed preclinical behavioral, histopathological, infarct volume, biochemical assays change in from multiple animal models, examining mechanisms of neuroprotection, pharmacokinetic profiles, safety data, and therapeutic window analyses for both individual and combination therapy approaches.

Results:

The hypothermia group showed pronounced neurological impairment, motor and cognitive deficits, increased oxidative stress- ↑LPO, ↓SOD, ↓GSH, elevated blood brain barrier permeability, and larger infarct volumes. All treatment groups demonstrated improvement across these measures, with the hypothermia + metformin + vitamin E + CoQ10 combination producing the most robust neuroprotection, combination treatment shows significant (p < 0.05) data as compared to individual treatment groups. Triple therapy improved motor coordination and memory, reduced oxidative injury, lowered Evans Blue extravasation and cerebral edema, and markedly decreased infarct size. Histopathological findings confirmed reduced neuronal degeneration and better preservation of cortical and hippocampal regions.

Conclusions:

The complementary mechanisms and synergistic interactions of metformin along with the therapeutic hypothermia support clinical translation of combination protocols. Overall, metformin, vitamin E and CoQ10 exhibited synergistic neuroprotective effects when used together, outperforming monotherapies. This combination represents a promising adjunct to therapeutic hypothermia for mitigating early hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in neonates.

Authors

Corresponding Author

Rajat Singh Rathore

History

Received 10 November 2025

Revised 26 November 2025

Accepted 03 December 2025

Keywords

Neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, Oxidative stress, Vitamin E, Coenzyme Q10, Neuroprotection, Antioxidants, Synergistic therapy, Metformin.

Open Access

This is an open access article under the CC BY license https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Funding

INTRODUCTION

Neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) [1,2], develops when the neonatal brain is subjected to insufficient oxygenation and impaired cerebral blood flow during late gestation, labor, delivery, or the early postnatal phase. Its clinical manifestations are highly variable, encompassing mild signs such as irritability and transient hypotonia to severe forms of encephalopathy characterized by frequent seizures, marked alterations in consciousness, and profound deficits in motor function [3]. The pathophysiology of HIE is driven by a complex, multi-stage cascade of cellular and molecular disturbances initiated immediately after the hypoxic-ischemic insult [4]. This biphasic nature of injury provides a critical therapeutic window for neuroprotective interventions.

The long-term consequences of HIE are profound, with survivors frequently experiencing cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, epilepsy, and sensory impairments that significantly impact quality of life and impose substantial socioeconomic burdens on families and healthcare systems [5]. Currently, therapeutic hypothermia remains the only established neuroprotective treatment for moderate to severe HIE in term and late preterm infants [6]. However, despite its proven efficacy, therapeutic hypothermia provides only modest neuroprotection, with approximately 45–50% of treated infants still experiencing death or major disability, highlighting the critical need for adjunctive or alternative therapeutic strategies [7]. Furthermore, hypothermia primarily targets the secondary phase of injury through metabolic suppression but does not directly address the underlying molecular mechanisms of neuronal death, including oxidative stress, inflammation, and excitotoxicity that contribute to ongoing brain damage [8,9].

Recent clinical trials investigating adjunctive therapies such as erythropoietin, melatonin, and xenon have shown mixed results, with some promising preclinical findings not translating to significant clinical benefits [10–13].

The primary phase is characterized by immediate cell death through necrosis, particularly in regions with high metabolic demand such as the basal ganglia, thalamus, and perirolandic cortex [14,15]. The secondary injury phase is particularly relevant to oxidative stress mechanisms, as reperfusion paradoxically increases reactive oxygen species generation while cellular antioxidant defenses remain compromised [15,16].

Reactive oxygen species play a central role in the pathogenesis of hypoxic-ischemic brain injury, with their generation occurring through multiple pathways during both the primary and secondary phases of injury [17,18]. The activation of enzymes such as xanthine oxidase, NADPH oxidase, and cyclo-oxygenase contributes to ROS production during the reperfusion phase [18,19].

ROS-mediated damage extends beyond lipid peroxidation to include protein oxidation and DNA damage. A third phase may occur days later as inflammatory cells infiltrate damaged brain regions and activated microglia generate additional ROS through NADPH oxidase activation. This prolonged oxidative stress contributes to the expansion of brain injury beyond the initial areas of damage and provides multiple opportunities for therapeutic intervention [18,20–22].

Vitamin E and CoQ10 have emerged as particularly promising candidates due to their excellent safety profiles, favorable pharmacokinetic properties, and demonstrated neuroprotective effects in experimental models of HIE. Vitamin E, a lipophilic antioxidant that protects cellular membranes from lipid peroxidation, and CoQ10, which serves dual roles as a mitochondrial electron transport chain component and potent antioxidant, represent mechanistically distinct yet complementary approaches to combating oxidative stress in neonatal HIE [23–25]. Earlier, simultaneous administration of metformin and CoQ10 has been reported to enhance anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic action [26–28], indicating CoQ10 contributes to metformin action.

Data on their combined effects on neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy injury are lacking. Therefore, the aim of the present study is to evaluate the effects of metformin, vitamin E and CoQ10 in neonatal rat model of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy and associated cognitive complications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Metformin was obtained as a gift sample from Emcure Pharmaceutical, Pune, Maharashtra, whereas CoQ10 was purchased by SV Agro Mumbai, Maharashtra. Vitamin E was procured from Matrix Life Science Private Limited (Aurangabad, Maharashtra). All other chemicals and reagents used in this work were of analytical grade.

Experimental Animals

A total of 120 Wistar rat pups were used in the study with 40 rat pups (4 pups per group, 5 groups and 2 genders) each for oxidative stress markers, behavioral analysis and neurological analysis. Animal care, anesthesia, and surgical procedures was performed in accordance with the guidelines for animal care and use, monitored for overall appearance, failure to thrive, and any neurological defects from birth until the end of the experiment.

Wistar rat pups (postnatal day 1) were used. Animal experiment was carried out in Madhyanchal Professional University Bhopal (MP) India, after due permission of institutional animal ethics committee reference no. PCP/IAEC/44, which is registered with the committee for Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animal (CPCSEA), government of India. Animals were housed under standard laboratory conditions.

INDUCTION OF HIE

Induction of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy [HIE] was a induced in rat pups via unilateral carotid artery ligation followed by a low oxygen environment on PND 7 (Table 1).

| S. no. | Groups | Treatment | Number of (Pups) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Group I | SHAM Operated-Control | 24 |

| 2. | Group II | HIE + Hypothermia [HYPO] | 24 |

| 3. | Group III | HIE + Hypothermia + Metformin [MET] + Vitamin E | 24 |

| 4. | Group IV | HIE + Hypothermia+ MET + CoQ10 | 24 |

| 5. | Group V | HIE + Hypothermia + MET + Vitamin E + CoQ10 | 24 |

Briefly, pups were anesthetized with 5% inhaled isoflurane followed by 2% for maintenance. The right common carotid artery was carefully isolated from the vagus nerve and ligated. The wound was closed with surgical glue and the pups were allowed to recover in a cold-water bath with a set temperature of 37°C for 20 min and rectal temperature was recorded throughout the duration. Pups were then placed in a hypoxic chamber (92% N, 8% O2) for 120 min [29].

During the hypoxia procedure, surface body temperature was controlled using cold water bath with a set temperature of 37°C and rectal temperature was recorded throughout the time. Subsequently, pups were allowed to recover for 20 min followed by administration of vehicle (0.9% saline) or vitamin E or metformin or CoQ10, after which pups were kept at room temperature (Table 2). Euthanasia on PND 14, pups were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) via ip injection and then decapitated. The brain of each pup were dissected out, weighed, washed with chilled saline, and stored at 80°C for oxidative stress markers.

| Drug | MET | CoQ10 | Vitamin E | Ketamine | Xylazine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose | 200 mg/kg | 200 mg/kg | 100 mg/kg | 70 mg/kg | 10 mg/kg |

| Site | Oral | Oral | Oral | Intramuscular | Intra muscular |

| Volume | 5 ml/kg | 5 ml/kg | 5 ml/kg | 5 ml/kg | 5 ml/kg |

Behavioral Assessments

NORT (Novel Object recognition test) is a sensitive, reliable memory assessment tool that can detect suitable behavioral & cognitive effects. This test is based on the natural tendency of rodents to investigate a novel object instead of a familiar one [30]. NORT was performed to assess the ability to recognize two different objects. Y-Maze and elevated plus maze was performed to analyse the behavioral assessments [31,32].

Biochemical Assays

At PND 14, pups were sacrificed and decapitated; the brain was rapidly dissected out and washed with cold isotonic buffer, then 1 gm of tissues was taken in 10 ml of cold isotonic buffer and homogenized at 3000 rpm for 5 min in a teflon shaft homogenizer. The homogenate was then centrifuged at 3500 rpm at 2–8°C for 10 min. The homogenate (upper layer) was used for the estimation of GSH, LPO estimation. For SOD, to the 500 µl of homogenate (supernatant) 800 µl of ice-cold chloroform/ethanol (37.5/62.5 v/v) was added to inactivate manganese (Mn) and iron (Fe) superoxide dismutase isoforms and shaken for 30 sec, then centrifuged the mixture at 2500 rpm at 2–8°C for 10 min, then the homogenate (supernatant) was used for the estimation of SOD.

Blood–Brain Barrier (BBB) Permeability Assessment

BBB integrity was evaluated by measuring of extra-vascular Evans’s blue (EB) concentration while the rats were anesthetized. On PND 14, brain vascular permeability was measured by injection of Evans blue dye via tail vein, following the anaesthesia, 20 mg/kg of Evans blue dye 2% (1 ml/kg) in saline was injected thought the tail vein of the rat. After 30 min of injection, the thorax was opened under deep anaesthesia and animal were perfused with saline (200–300 ml) through left ventricle until colourless fluid flowed from the right atrium to remove the intravascular Evans blue dye. The brain was immediately removed, weighed rapidly, and homogenized in 1 ml of 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer saline (PBS) and then centrifuged at 1000 g for 15 minutes. Trichloroacetic acid (0.7 mL of 100% solution) was added to 0.7 mL supernatant. The mixture was allowed to incubating 14°C for 18 h and after centrifuged again at 1000 g for 30 minutes. The amount of EB in the supernatant was determined spectrophotometrically at 610 nm by comparison against readings obtained from standard solution [33].

TTC [2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride] Staining for Infarct Volume

Rats were sacrificed, the brain promptly isolated, and coronal slices (2 mm) were cut and stained with 2% TTC for 30 min at room temperature. Slices were fixed in 10% formalin overnight and scanned. Each slice was evaluated for infarct area using Image J software 1.30 V. Areas of infarct for each slice calculate as infarct area multiplied by 100 and divided by the total area of that slice (Infarct area (mm3) × 100/total area (mm3) of that slice) all sections are added together to obtain the infarct area which was divided by the no. of brain slice to get the total infarct area of per brain in % [34].

Histopathological Evaluation

After pups have been decapitated, the brain was rapidly dissected out, washed immediately with saline, and fixed in 10% buffered formalin. The brain, stored in 10% formalin, was embedded in paraffin and sections (5 mm) were cut and stained using hematoxylin and eosin. Brain sections were observed under a microscope (LABOMED CXR 3) for any histological changes [35,36]. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining was performed to assess neuronal morphology, edema, and inflammatory cell infiltration.

RESULTS

Behavioral Assessments

Effect of Drug on Neurological Deficit Measurement

Sensorimotor score was evaluated for neurological deficits and of which the experimental groups were identified and summations of test score were assessed. In all five parameters of neurological deficit, low scoring in hypothermia [HYPO] group as compared to SHAM was observed. However, this reduction was significant only in three scorings for forepaw stretching, body proprioception & response to touching vibrissae (Table 3).

| Groups | Spontaneous activity (Median value) | Symmetry in the movement of 4 limbs (Median value) | Forepaw outstretching (Median value) | Body proprioception (Median value) | Response to touching vibrissae (Median value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHAM | 2.50 | 2.50 | 3.00 | 2.50 | 3.00 |

| HIE + Hypothermia [HYPO] | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 a | 0.50 a | 0.00 a |

| HIE + Hypothermia + MET + Vit E | 1.50 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| HIE + Hypothermia + MET + CoQ10 | 2.00 | 2.50 a b | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| HIE + Hypothermia + MET + Vit E + CoQ10 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

Administration of metformin with vitamin E or CoQ10 resulted in a measurable improvement in neurological performance. The metformin + CoQ10 group demonstrated the strongest recovery in limb symmetry and spontaneous activity, reflecting enhanced motor coordination and muscle tone. In contrast, the metformin + vitamin E treated animals showed moderate improvements but did not fully restore proprioceptive or reflexive responses.

Notably, the triple therapy group along with the therapeutic hypothermia (metformin + vitamin E + CoQ10) displayed the most pronounced enhancement across all five neurological domains. This group approached near-normal scores, indicating substantial protection of neural pathways involved in sensory-motor processing. The improvement suggests a synergistic neuroprotective effect that effectively counteracts hypoxia-induced neuronal injury.

BIOCHEMICAL ASSAYS

Effect of Treatment Drug on Oxidative Stress Markers

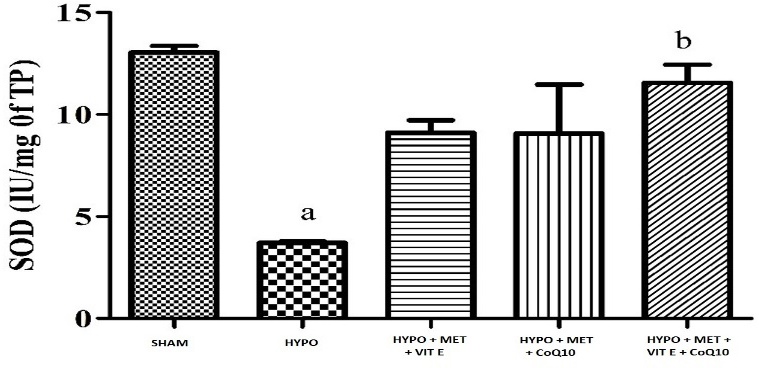

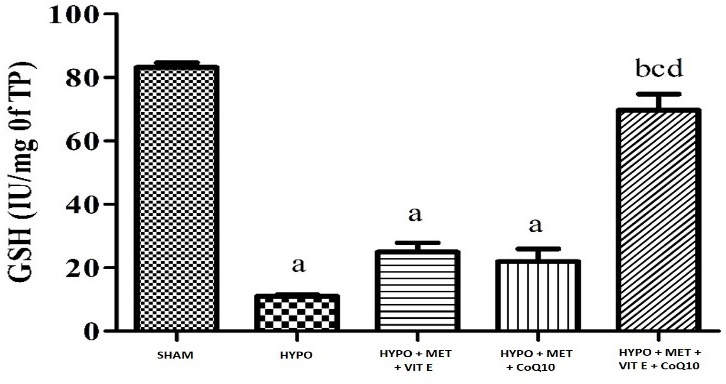

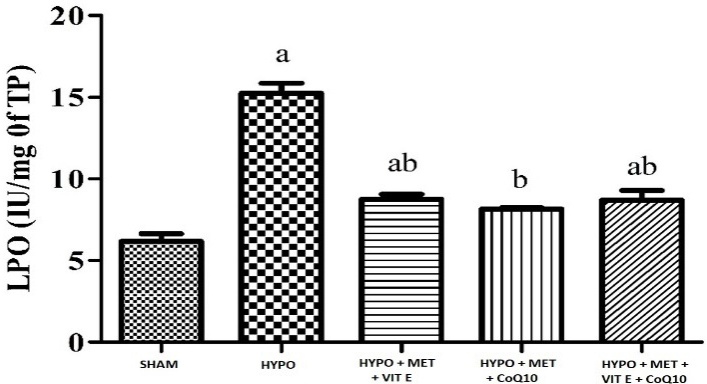

Challenging the animals with HIE followed by treatment with hypothermia significantly caused oxidative damage (Table 4) as indicated by increased in lipid peroxidation (MDA level), it caused by oxidative damage significant in brain cortex of HYPO group while decreased superoxide dismutase (SOD), and glutathione (GSH) activity in whole brain region. Pre-treatment with MET (200 mg/kg), Vit E (100 mg/kg) and CoQ10 (200 mg/kg) significantly restored depleted GSH (glutathione) and catalase activity as well as attenuated elevated lipid peroxidation of the brain, as compared to their respective control and HYPO group (Figures 1–3).

| Groups | SOD (IU/mg TP) | GSH (µg/mg TP) | LPO (µM/mg TP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SHAM | 13.04 ± 0.32 | 83.20 ± 1.49 | 6.16 ± 0.47 |

| HIE + Hypothermia [HYPO] | 3.71 ± 0.07 a | 11.05 ± 0.48 a | 15.24 ± 0.61 a |

| HIE + Hypothermia + MET + Vit E | 9.10 ± 0.60 | 24.68 ± 2.91 a | 8.76 ± 0.29 a b |

| HIE + Hypothermia + MET + CoQ10 | 9.07 ± 2.40 | 21.96 ± 4.02 a | 8.15 ± 0.07 b |

| HIE + Hypothermia + MET + Vit E + CoQ10 | 11.56 ± 0.88 b | 69.73 ± 5.06bcd | 8.70 ± 0.58 a b |

Figure 1 - Graph depicting SOD level in the brain. All data were expressed as Mean ± SEM. Statistical difference were determined by One-way ANOVA followed be Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison test. Where the values are expressed as Mean ± SEM (n = 4). Where ap < 0.05 vs SHAM, bp < 0.05 vs HYPO, cp < 0.05 vs MET + Vit E and dp < 0.05 vs MET + Vit E + CoQ10.

Figure 2 - Graph depicting GSH level in the brain. All data were expressed as Mean ± SEM. Statistical difference were determined by One-way ANOVA followed be Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison test. Where the values are expressed as Mean ± SEM (n = 4). Where ap < 0.05 vs SHAM, bp < 0.05 vs HYPO, cp < 0.05 vs MET + Vit E and dp < 0.05 vs MET + Vit E + CoQ10.

Figure 3 - Graph depicting LPO level in the brain. All data were expressed as Mean ± SEM. Statistical difference were determined by One-way ANOVA followed be Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison test. Where the values are expressed as Mean ± SEM (n = 4). Where ap < 0.05 vs SHAM, bp < 0.05 vs HYPO, cp < 0.05 vs MET + Vit E and dp < 0.05 vs MET + Vit E + CoQ10.

Effect on Treatment on BBB Permeability

The analysis of BBB permeability was measured by Evans Blue [EB] dye content in rat brain which was measured by spectroscopy method. The EB dye content was higher in the brain of the HYPO group compared with sham group and all treatment group, while combination treatment shows significant lower level at EB dye as compared to individual treatment groups. EB quantification revealed severe BBB disruption in the HIE + Hypothermia group, with dye extravasation nearly doubling compared to sham animals.

MET + Vit E and MET + CoQ10 treatments significantly reduced dye leakage, indicating partial restoration of endothelial integrity. CoQ10 containing therapy again outperformed Vit E alone, likely due to its mitochondrial stabilizing effect on endothelial cells.

The MET + Vit E + CoQ10 therapy along with the therapeutic hypothermia demonstrated the most profound reduction in EB extravasation, surpassing all other groups and returning BBB permeability levels close to those of uninjured controls. These findings strongly support the combination’s protective influence on vascular and tight junction structures (Table 5).

| Groups | Evans blue dye (µg/ml) |

|---|---|

| SHAM | 2.38 ± 0.02 |

| HIE + Hypothermia [HYPO] | 4.54 ± 0.09 a |

| HIE + Hypothermia + MET + Vit E | 3.13 ± 0.11 b |

| HIE + Hypothermia + MET + CoQ10 | 2.39 ± 0.19abc |

| HIE + Hypothermia + MET + Vit E + CoQ10 | 2.24 ± 0.09 b c |

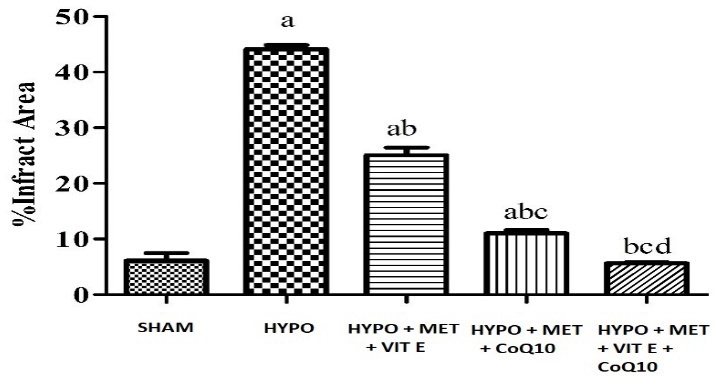

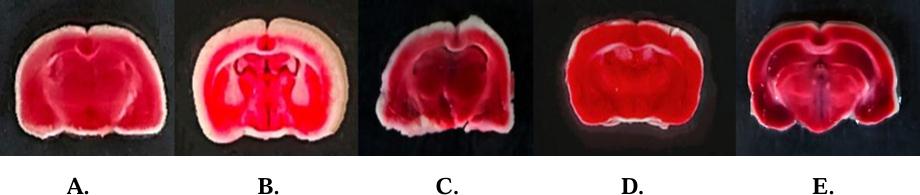

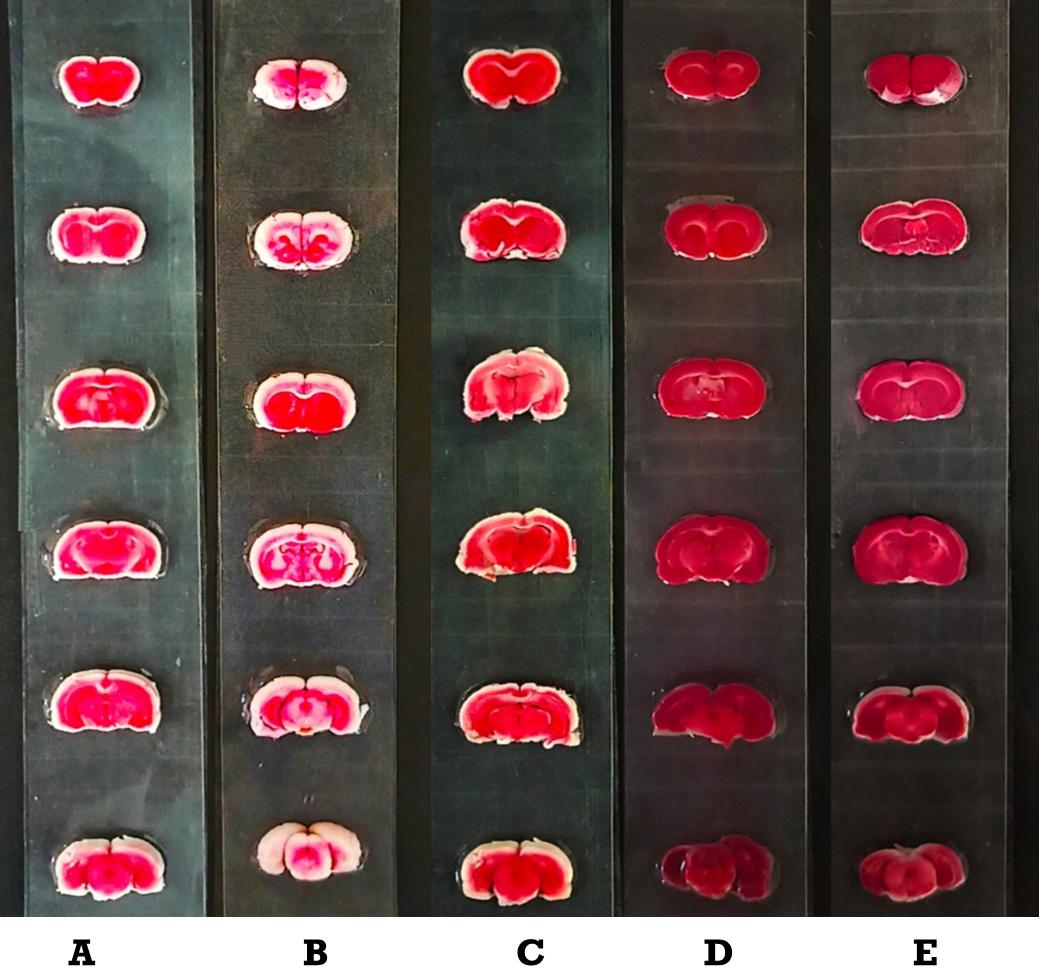

TTC Staining for Infarct Volume

Ischemia injury causes infraction in the brain regions. In the HYPO group show severe cerebral infarction due to extensive damage inflicted by HYPO injury as compared with SHAM group. Pre-treatment with MET, Vit E and CoQ10 showed significant reduction in infarct area as compared with HYPO group. Whereas pre-treatment with MET + Vit E + CoQ10 along with hypothermia showed significant reduction in infarct area as compared with HYPO and MET, Vit E and CoQ10 treated group (Table 6, Figure 4).

| Groups | % Brain infarct area |

|---|---|

| SHAM | 6.11 ± 1.36 |

| HIE + Hypothermia [HYPO] | 44.11 ± 0.76 a |

| HIE + Hypothermia + Met + Vit E | 25.07 ± 1.37 a b |

| HIE + Hypothermia + Met + CoQ10 | 11.00 ± 0.63abc |

| HIE + Hypothermia + Met + Vit E + CoQ10 | 5.64 ± 0.21bcd |

Figure 4 - Graph depicting % brain infarct area All data were expressed as Mean ± SEM. Statistical difference was determined by One-way ANOVA followed be Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison test. The values are expressed as Mean ± SEM (n = 4). Where ap < 0.05 vs SHAM, bp < 0.05 vs HYPO, cp < 0.05 vs HYPO + MET + Vit E and dp < 0.05 vs HYPO + MET + CoQ10.

Infarct analysis (Coronal brain sections 2 mm), stained with 2% TTC, showing stained brain slices infarct area after 15 min bilateral common carotid artery occlusions followed by 24 h reperfusion in SHAM, HYPO and treatment groups pups (Figure 5). The red area represents the non-ischemic (viable tissue) area (Figure 6), whereas the white area indicates ischemic area (non-viable tissue) in the coronal section.

Figure 5 - Effect of MET, Vit E and CoQ10 on brain infarction Where A: SHAM; B: HYPO; C: HYPO + MET + Vit E; D: HYPO + MET + CoQ10; E: HYPO + MET + Vit E + CoQ10.

Figure 6 - Cerebral infarction. A: SHAM; B: HYPO; C: HYPO + MET + Vit E; D: HYPO + MET + CoQ 10; E: HYPO + MET + Vit E + CoQ10.

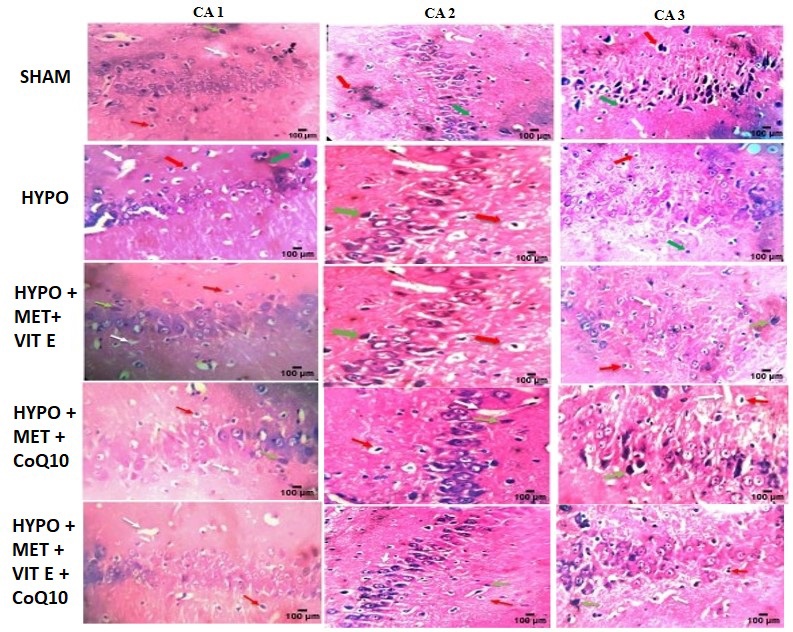

Histopathological Evaluation

Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) analysis of brain tissues from SHAM, HYPO and treated rats displayed normal histopathological structure of the hippocampus. There was a reduction in the pyramidal cell count in Cornu ammonis (CA) (CA1, CA2, and CA3) regions in the HYPO group compared to the SHAM and other treatment groups (Figure 7). Pyramidal cells also displayed disarrangements, degeneration, and pyknosis of their nuclei, as well as the loss of pyramidal cells, which left empty spaces filled with vacuolations in the surrounding neutrophils. This group’s hippocampus revealed a significant decrease in the number of cells in all layers, as well as granular cell disarrangements, the appearance of numerous apoptotic cells, and darkly coloured nuclei with cytoplasm vacuolation [36,37].

In treatment group there was increased in the pyramidal cell count in CA1 area compared with SHAM control group. Histopathological examination revealed severe neuronal loss, cytoplasmic vacuolation, shrunken hyperchromatic nuclei and extensive cellular disorganization in the HIE + Hypothermia group, particularly in CA1–CA3 hippocampal regions (Table 7).

| Group | CA 1 | CA 2 | CA 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| SHAM | 80.17 ± 7.33 | 96.17 ± 9.75 | 85.50 ± 2.14 |

| HIE + Hypothermia [HYPO] | 39.67 ± 5.46 a | 40.17 ± 8.53 a | 48.33 ± 2.81 a |

| HIE + Hypothermia + MET + Vit E | 46.17 ± 7.04 a | 54.67 ± 7.56 a | 58.83 ± 2.81 a |

| HIE + Hypothermia + MET + CoQ10 | 51.00 ± 6.90 a | 68.67 ± 9.48 a | 69.17 ± 3.78 a |

| HIE + Hypothermia + MET + Vit E + CoQ10 | 67.50 ± 9.82 b | 87.33 ± 7.15 | 76.83 ± 3.91 |

Therapeutic groups displayed varying degrees of neuronal preservation:

- MET + Vit E showed moderate protection

- MET + CoQ10 demonstrated greater neuronal survival with reduced pyknosis

- Triple therapy[MET + Vit E + CoQ10] resulted in nearly normal hippocampal architecture

The triple-treated animals exhibited significantly higher pyramidal cell counts, reduced vacuolization, and minimal inflammatory infiltration. Overall structural integrity resembled the sham group, confirming strong histological neuroprotection.

Light microscopic examination of hematoxylin and Eosin (H & E) stained sections in all groups showed (Red arrow) number of pyknotic nuclei, white arrow showed necrotic part and green arrow showed vacuole. SHAM – Operated group showing normal histological picture and no neuronal loss was observed. In HYPO marked degeneration and disarrangement in pyramidal cell structure, increased intracellular space, pyknotic nuclei, vacuolations and neuronal loss was observed. MET treatment group showing moderate reversal of neuronal damage and few vacuolations. Vit E group showing marked reversal of neuronal damage and partial neuronal loss was observed. Whereas triple therapy [MET + Vit E + CoQ10] group showing protection of brain cells from ischemic damage, improvement in cellular structure and more effective as compared with individual treatment.

DISCUSSION

The developing neonatal brain exhibits heightened susceptibility to oxidative stress due to several unique developmental characteristics that distinguish it from the mature brain. The high rate of brain growth during the perinatal period is associated with elevated oxygen consumption and metabolic activity, creating an environment prone to oxidative stress when oxygen delivery is compromised. Additionally, the process of myelination, which is actively occurring in the neonatal brain, involves the synthesis of lipid-rich myelin sheaths that are particularly vulnerable to lipid peroxidation [11]. This study demonstrates that metformin, vitamin E, and CoQ10 offer significant neuroprotection against neonatal HIE. The triple therapy showed synergistic benefits by targeting mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and BBB breakdown. The combined antioxidant and mitochondrial support provided by these agents appears to be the key mechanism.

Metformin further augmented neuroprotection by ameliorating mitochondrial dysfunction, reducing inflammatory signaling, and enhancing cellular resilience against metabolic collapse. However, the most profound protective effects emerged from the triple-combination regimen, which exhibited synergistic restoration of antioxidant defenses (SOD, GSH), marked suppression of lipid peroxidation (LPO), and normalization of BBB integrity as evidenced by reduced Evans blue extravasation [38].

The treatment groups demonstrated significant reductions in infarct volume on TTC staining, accompanied by preservation of pyramidal neuron density within the CA1–CA3 hippocampal regions, areas critically vulnerable to hypoxic-ischemic injury. Histopathological analyses confirmed reduced neuronal pyknosis, diminished cytoplasmic vacuolation, and attenuation of inflammatory cell infiltration in combination-treated animals, indicating effective mitigation of both necrotic and apoptotic pathways. Behavioral assessments including neurological deficit scoring, Y-maze performance and NORT outcomes further corroborated that antioxidant therapy yielded functional improvements consistent with enhanced neuronal survival and synaptic integrity [39].

Collectively, the results underscore that neonatal HIE is driven by a convergent cascade involving oxidative stress, mitochondrial impairment, excitotoxicity, neuroinflammation, BBB disruption, and secondary energy failure [40,41]. The superior efficacy of metformin + vitamin E + CoQ10 suggests that targeting multiple pathophysiological checkpoints simultaneously is substantially more effective than monotherapy approaches. The observed synergistic interaction supports the hypothesis that combination antioxidant therapy can broaden the therapeutic window, enhance mitochondrial resilience, stabilize membrane structures and better preserve neurovascular unit function.

CONCLUSION

The ultimate goal of providing comprehensive neuroprotective therapy that combines the proven benefits of therapeutic hypothermia with the complementary mechanisms of antioxidant protection represents a realistic and achievable advance in neonatal care. The evidence presented in this research strongly supports the continued development of vitamin E and CoQ10, both individually and in combination, as promising therapeutic strategies for one of the most devastating conditions affecting newborn infants. Further studies are required to evaluate the long-term treatment effect of this combination & estimation of cognitive biomarkers would be interesting. In conclusion, the triple therapy of metformin, vitamin E, and CoQ10 significantly mitigates hypoxic-ischemic brain injury by targeting key mechanisms underpinning oxidative, metabolic, and inflammatory damage. The results support the emerging paradigm that combination antioxidant therapy represents a promising, mechanistically rational, and clinically relevant strategy for improving neurological outcomes in neonatal HIE.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Author’s Contribution

Deepa Iyer and Rita Mourya designed the model and analyzed the data; Rajat Singh Rathore carried out the experiments and data collection; Naveen Gupta supervised the project and provided direction. All four authors have contributed significantly to the research conception and design, interpretation of data, and critical revision of the manuscript.

Acknowledgment

Authors would like to express sincere gratitude to Madhyanchal Professional University, Bhopal, for providing the necessary facilities and a supportive environment to conduct this research. Authors are deeply thankful to Patel College of Pharmacy management and staffs for their encouragement and administrative support throughout the project.

REFERENCES

| [1] | Kurinczuk JJ, White-Koning M, Badawi N. Epidemiology of neonatal encephalopathy and hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86(6):329–338. Doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.05.010. |

| [2] | Lee AC, Kozuki N, Blencowe H, Vos T, Bahalim A, Darmstadt GL, et al. Intrapartum-related neonatal encephalopathy incidence and impairment at regional and global levels for 2010 with trends from 1990. Pediatr Res. 2013; 74 Suppl 1(Suppl 1): 50–72. Doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.206. |

| [3] | Sarnat HB, Sarnat MS. Neonatal encephalopathy following fetal distress. A clinical and electroencephalographic study. Arch Neurol. 1976;33(10):696–705. Doi: 10.1001/archneur.1976.00500100030012. |

| [4] | Ferriero DM. Neonatal brain injury. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(19):1985–1995. Doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041996. |

| [5] | Perlman JM. Summary proceedings from the neurology group on hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Pediatrics. 2006; 117(3 Pt 2): S28–33. Doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0620E. |

| [6] | Jacobs SE, Berg M, Hunt R, Tarnow-Mordi WO, Inder TE, Davis PG. Cooling for newborns with hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013(1):CD003311. Doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003311.pub3. |

| [7] | Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Ehrenkranz RA, Tyson JE, McDonald SA, Donovan EF, et al. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Whole-body hypothermia for neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(15):1574–1584. Doi: 10.1056/NEJMcps050929. |

| [8] | Douglas-Escobar M, Weiss MD. Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: a review for the clinician. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(4):397–403. Doi: 10.1001/jama-pediatrics.2014.3269. |

| [9] | McBain K, Renton LBM. Computer-Assisted Cognitive Rehabilitation and Occupational Therapy. Br J Occup Ther. 1997;60(5):199–204. Doi: 10.1177/030802269706000503. |

| [10] | Robertson NJ, Tan S, Groenendaal F, van Bel F, Juul SE, Bennet L, et al. Which neuroprotective agents are ready for bench to bedside translation in the newborn infant? J Pediatr. 2012;160(4):544–552.e4. Doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.12.052. |

| [11] | Perrone S, Tataranno LM, Stazzoni G, Ramenghi L, Buonocore G. Brain susceptibility to oxidative stress in the perinatal period. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28 Suppl 1:2291–2295. Doi: 10.3109/14767058.2013.796170. |

| [12] | Tagin M, Abdel-Hady H, ur Rahman S, Azzopardi DV, Gunn AJ. Neuroprotection for Perinatal Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. J Pediatr. 2015;167(1):25–28. Doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.02.056. |

| [13] | Nunez C, Stephan-Otto C, Arca G, Agut T, Arnaez J, Cordeiro M, et al. Neonatal arterial stroke location is associated with outcome at 2 years: a voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2022;107(1):45–50. Doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-320400. |

| [14] | Buonocore G, Perrone S, Bracci R. Free radicals and brain damage in the newborn. Biol Neonate. 2001;79(3–4): 180–186. Doi: 10.1159/000047088. |

| [15] | Martini S, Castellini L, Parladori R, Paoletti V, Aceti A, Corvaglia L. Free radicals and neonatal brain injury: From underlying pathophysiology to antioxidant treatment perspectives. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021;10(12):2012. Doi: 10.3390/antiox10122012. |

| [16] | Qin X, Cheng J, Zhong Y, Mahgoub OK, Akter F, Fan Y, et al. mechanism and treatment related to oxidative stress in neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Front Mol Neurosci. 2019;12:88. Doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2019.00088. |

| [17] | Aloe L, Rocco ML, Bianchi P, Manni L. Nerve growth factor: from the early discoveries to the potential clinical use. J Transl Med. 2012;10:239. Doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-239. |

| [18] | McCord JM. Oxygen-derived free radicals in postischemic tissue injury. N Engl J Med. 1985;312(3):159–163. Doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501173120305. |

| [19] | Pourcyrous M, Leffler CW, Bada HS, Korones SB, Busija DW. Brain superoxide anion generation in asphyxiated piglets and the effect of indomethacin at therapeutic dose. Pediatr Res. 1993;34(3):366–369. Doi: 10.1203/00006450-199309000-00025. |

| [20] | Schumann P, Touzani O, Young AR, Verard L, Morello R, MacKenzie ET. Effects of indomethacin on cerebral blood flow and oxygen metabolism: a positron emission tomographic investigation in the anaesthetized baboon. Neurosci Lett. 1996;220(2):137–141. Doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(96)13210-9. |

| [21] | Halliwell B. Oxidative stress and neurodegeneration: where are we now? J Neurochem. 2006;97(6):1634–1658. Doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03907.x. |

| [22] | Hagberg H, Mallard C, Rousset CI, Thornton C. Mitochondria: hub of injury responses in the developing brain. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(2):217–232. Doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70261-8. |

| [23] | Mavelli I, Rigo A, Federico R, Ciriolo MR, Rotilio G. Superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase and catalase in developing rat brain. Biochem J. 1982;204(2):535–540. Doi: 10.1042/bj2040535. |

| [24] | Crack PJ, Taylor JM. Reactive oxygen species and the modulation of stroke. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38(11):1433–1444. Doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.01.019. |

| [25] | Kumar A, Mittal R, Khanna HD, Basu S. Free radical injury and blood-brain barrier permeability in hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Pediatrics. 2008;122(3):e722–727. Doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0269. |

| [26] | Jhun JY, Lee SH, Kim SY, Na HS, Kim EK, Kim JK, et al. Combination therapy with metformin and coenzyme Q10 in murine experimental autoimmune arthritis. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2016;38(2):103–112. Doi: 10.3109/08923973.2015.1122619. |

| [27] | Al-Kuraishy HM, Al-Gareeb AI, Shams HA, Al-Mamorri F. Endothelial dysfunction and inflammatory biomarkers as a response factor of concurrent coenzyme Q10 add-on metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Lab Physicians. 2019;11(04):317–322. Doi: 10.4103/JLP.JLP_123_19. |

| [28] | Sun IO, Jin L, Jin J, Lim SW, Chung BH, Yang CW. The effects of addition of coenzyme Q10 to metformin on sirolimus-induced diabetes mellitus. Korean J Intern Med. 2019;34(2):365–374. Doi: 10.3904/kjim.2017.004. |

| [29] | Mandloi AS, Malviya C, Upasani CD, Dhote V, Upaganlawar AB. Impact on post-stroke injury: Co-administration of metformin and CoQ10 in cerebral ischemia injury. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2025;15(01):206–215. 10.7324/JAPS.2024.201853. |

| [30] | Wahl F, Allix M, Plotkine M, Boulu RG. Neurological and behavioral outcomes of focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Stroke. 1992;23(2):267–272. Doi: 10.1161/01.str.23.2.267. |

| [31] | Nade VS, Kawale LA, Dwivedi S, Yadav AV. Neuroprotective effect of Hibiscus rosa sinensis in an oxidative stress model of cerebral postischemic reperfusion injury in rats. Pharm Biol. 2010;48(7):822–827 Doi: 10.3109/13880200903283699. |

| [32] | Sharma AC, Kulkarni SK. Evaluation of learning and memory mechanisms employing elevated plus-maze in rats and mice. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1992;16(1):117–125. Doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(92)90014-6. |

| [33] | Gursoy-Ozdemir Y, Bolay H, Saribaş O, Dalkara T. Role of endothelial nitric oxide generation and peroxynitrite formation in reperfusion injury after focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2000;31(8):1974–1981. Doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.8.1974. |

| [34] | Bederson JB, Pitts LH, Germano SM, Nishimura MC, Davis RL, Bartkowski HM. Evaluation of 2, 3, 5-triphenyltetra-zolium chloride as a stain for detection and quantification of experimental cerebral infarction in rats. Stroke. 1986;17(6):1304–1308. Doi: 10.1161/01.str.17.6.1304. |

| [35] | Vannucci RC, Connor JR, Mauger DT, Palmer C, Smith MB, Towfighi J, et al. Rat model of perinatal hypoxic-ischemic brain damage. J Neurosci Res. 1999;55(2):158–63. Doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990115)55:2<158::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-1. |

| [36] | Dhote V, Balaraman R. Anti-oxidant activity mediated neuroprotective potential of trimetazidine on focal cerebral ischaemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2008; 35(5–6):630–637. Doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2008.04845.x. |

| [37] | Hazzaa SM, Abdelaziz SAM, Abd Eldaim MA, Abdel-Daim MM, Elgarawany GE. Neuroprotective potential of Allium sativum against monosodium glutamate-induced excitotoxicity: Impact on short-term memory, gliosis, and oxidative stress. Nutrients. 2020;12(4):1028. Doi: 10.3390/nu12041028. |

| [38] | Reed S, Taka E, Darling-Reed S, Soliman KFA. Neuroprotective effects of metformin through the modulation of neuroinflammation and oxidative stress. Cells. 2025;14(14):1064. Doi: 10.3390/cells14141064. |

| [39] | Einenkel AM, Salameh A. Selective vulnerability of hippocampal CA1 and CA3 pyramidal cells: What are possible pathomechanisms and should more attention be paid to the CA3 region in future studies? J Neurosci Res. 2024;102(1):e25276. Doi: 10.1002/jnr.25276. |

| [40] | Babbo CC, Mellet J, van Rensburg J, Pillay S, Horn AR, Nakwa FL, et al. Neonatal encephalopathy due to suspected hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy: pathophysiology, current, and emerging treatments. World J Pediatr. 2024;20(11):1105–1114. Doi: 10.1007/s12519-024-00836-9. |

| [41] | Dixon BJ, Reis C, Ho WM, Tang J, Zhang JH. Neuroprotective strategies after neonatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(9):22368–401. Doi: 10.3390/ijms160922368. |